If you were to be asked to recall the slope intercept formula, or the names of all the U.S. Presidents within the last 50 years, or even the phone numbers of your closest childhood friends, how well do you think you’d be able to remember these things? Assuming you’re not a mathematician (or working primarily with algebraic formulas in your day to day), a historian, or a child, you probably couldn’t recall any of those things very well. And that’s okay; you haven’t really had a reason to. Now, let me ask you another question: think back to the last large corporate training program, whether that be a workshop, seminar, or other type of training, and try to remember everything you were taught. Can you? My guess would be “not much,” and this is the dismal reality of one-time-training, because you should remember those things. They’re supposed to be helping you get better every day!

Now, before you dismiss this out of hand by saying “of course I don’t remember those things, why should I?” or “of course, my memory is getting worse because I’m getting older” let’s examine precisely why that is the case. Yes, it’s true, unfortunately, that memory worsens over time in general. In severe cases, aging can even lead to long-term diseases like dementia and Alzheimer’s, both of which attack and debilitate memory functions that can have extremely negative health consequences. But, for most people, memory — and its subsequent, gradual loss — is something we tend to take for granted. Looking at the first example of the algebra formula, it’s likely that unless you’ve used this particular formula recently, you would have had no reason to remember it. It was something learned long ago in a classroom far far away, and at the time it’s likely that at least one kid indignantly asked “when will I use this in real life?” The formula was learned then and there, and then once the class was passed, it fell by the wayside and got categorized as unimportant information. Then, that information was never accessed again — because you had no reason to use it — so eventually you forgot about it completely. This illustrates the first point about memory: repetition and application are keys to keeping things in front of the mind.

In order to truly learn something, you don’t just do it once.

The other major factor is that the information in the case of the algebra formula was probably somewhat “boring” to the average student. It probably wasn’t delivered in an overtly flashy manner — just a teacher with a projector and a couple of slides, explaining verbally what the formula is and why it matters. Not to mention you learned it while you were a kid, unconcerned with anything but the world outside the classroom, daydreaming of ball games and fun times with friends, not at all interested in the squiggly figures and letter-number combinations up on the screen. While an unadorned presentation of the material is useful in getting straight to the point, a “boring” education like this unfortunately means it’s not as prone to stick in the learner’s mind.

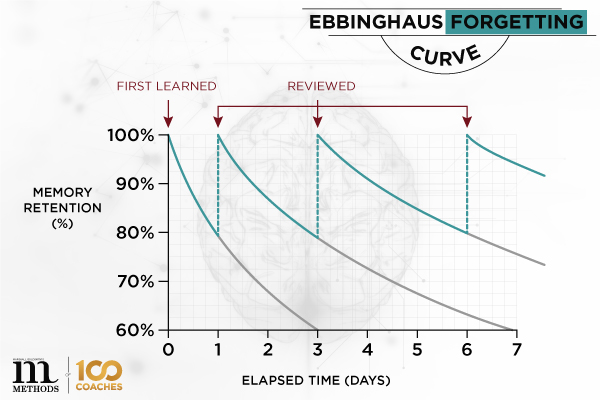

According to Practical Pie, “The Ebbinghaus forgetting curve is a graphical representation of the forgetting process. The curve demonstrates the declining rate at which information is lost if no particular effort is made to remember it. The forgetting curve was defined in 1885 by German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus (1850-1909) in his book Memory.”

What the Ebbinghaus Curve shows us is that the more exciting and relevant the knowledge is — including the way it’s presented — the better of a chance we have of remembering it. We’ve heard that different types of people are different kinds of “learners” and that speaks to this aspect of the forgetting curve. In order for information to stick in the mind, it has to be presented in an engaging way for each learner.

Another aspect of the Ebbinghaus Curve that is crucial to understand is that information tends to be better absorbed when it’s taught over time. This is related to the concept of repetition, but this is specifically known as spaced repetition. The theory goes that, if you keep periodically re-learning (or refreshing your knowledge), the concept will have a better chance of sticking in your mind. This is why incremental approaches to, say, studying for an exam are typically more fruitful than all-night cramming sessions. Think about it like practicing an instrument — you don’t suddenly become Mozart on the piano just because you practiced for 70 hours one week. You need time for the muscle memory to set in and become, well, memory. It is often more effective to practice for one hour a day, over 70 days, than 70 hours in a week.

The frequent, steady repetition of the activity is what makes learning or training something “second nature.”

In a business setting, we can apply the Ebbinghaus theory to training initiatives, which have historically been delivered in the form of seminars, one on one coaching sessions, workshops, or large-scale conferences. Consider this: How many times has your company or team gone to one of these training events — let’s say a conference that lasted 3 days — and came back jazzed up, chock-full of the latest and greatest in management thinking, only to have it all but completely forgotten within a matter of weeks once the normal torrent of daily workloads washes over this newly acquired wisdom? Unfortunately, this is all too common in most people’s experiences. Not only are conferences or workshops like these predicated on the very idea of a one-time-solution, but they’re typical “cram” sessions where so much is packed into so little time, that the recipients walk away feeling dazed by the mountain of brilliant insight they’ve just gained, but it’s largely spectacle; they’re hard pressed to remember every little thing they were taught. Often, they only remember a few key takeaways, which are usually just pieces of information that stuck with them personally because of some contextual or immediate relevance to their existing lives. This is not to say that workshops are bad — in fact, they can be life-changing for people who attend them, but there are limitations to what can be taught successfully and in a lasting way.

One way to remedy this is to engage employees and teams with online training, where videos can be viewed at a steady pace, and rewatch as many times as needed, as often as needed. Online training systems like Marshall Goldsmith’s Methods of 100 Coaches also feature learning retention tools such as quizzes, interactive scenarios deploying skills learned from the lessons, and accountability and compliance features to ensure knowledge absorption. Not only that, but these lessons are delivered in high-quality videos that are short enough to watch in one easy sitting, and entertaining enough to bring you back to watch them again. You also won’t get bored with the instructors: our roster of world-class leadership experts, CEOs, and executive coaches know how to deliver their information in a way that people want to hear, and the variety of teachers’ Methods users get to view makes for a unique and engaging experience that never stagnates. Get access today and see the difference for yourself and your team.

As much as we’d all like to be able Benjamin-Button our ways back to childhood, reversing the steady creep of crow’s feet and creaky joints, we do have to accept that memory is a transient thing, a constantly fading horizon on which we must keep our eyes peeled intentionally in the areas where it matters. While the forgetting curve won’t be going away anytime soon, you can combat it in a number of ways, especially with online training available to you 24/7, 365 like Methods.